TCF 2020 Virtual Season · Music from the Barn

Mozart

Program

Piano Trio in B-flat major, K. 502 (1786) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) I. Allegro II. Larghetto III. Allegretto- Jorja Fleezanis, violin

- Andre Emilianoff, cello

- Robert Helps, piano

- from the 1990 Token Creek Festival

- Rose Mary Harbison & Kangwon Kim, violin

- Allyson Fleck & John Harbison, viola

- Rafael Popper-Keizer, ‘cello

- from the 2004 Token Creek Festival

- performed on Jack Fry instruments at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Madison

- Ya-Fei Chuang, piano

- Rose Mary Harbison & Laura Burns, violin

- Jennifer Paulson, viola

- Parry Karp, 'cello

- Ross Gilliland, bass

- from the 2008 Token Creek Festival

Program Notes

Mozart’s music is easy to discuss in generalities, in superlatives, but more difficult to describe in specifics. The works on this program are redolent of the indescribable qualities in Mozart that give the impression, as a piece progresses, of doors opening suddenly (sometimes false or trap doors), winds bringing unexpected change, and above all the elusive quality of Unheimlichkeit, untranslatable from the German but expressing something uncanny, astounding, inexplainable, supernormal. This is a program of three extraordinary works from an extraordinary composer.

Mozart trios for piano, violin, and cello are less played, and less prized than his other chamber music, but they are a great collection of mainly late pieces, cooler and more abstract than his quartets and quintets for strings, less entertaining than his bracing serenades for winds, but with an aristocratic swagger of their own. The Trio in B-flat has a very satisfying end-loaded shape, something Mozart achieves in a number of pieces (especially in his Piano Concerto in F major), each movement progressively more distinct and memorable.

The opening Allegro is clear in presentation, architectural, with a winning use of one of Mozart’s unique formal shifts—the introduction of completely new material at the beginning of the working-out section. It is one of those Mozart movements that seems almost too satisfied with being perfect. Not so the slow movement, which immediately changes the point of address, more aria than song. The Finale is just first rate, up more than a notch, driving to its conclusion with arrogant assurance, the basic motive imitated in Mozart’s inimitable chord spacings.

The Quintet in D, K. 593 is from one of the sites, along with opera and piano concerto, that occasioned Mozart’s greatest inspirations — the String Quintet. What was it about adding another viola to the standard string quartet that appealed so much to this composer?

The first movement begins with an Introduction which sounds like an invitation to musical thinking. “Come with me,” says the composer as he offers six varied questions and receives six varied answers, the last finally becoming an archway into the piece. At the end of the movement the Introduction returns, this time the last answer is far more important than before, but unwilling to let it stand the composer blows it away with a “proper” conclusion to his allegro. This sets up a slow movement which has been long prized for its depth and beauty, but especially for one section, roughly the middle third of the piece, where both the harmony and the texture become unmoored. When normalcy returns, the listener cannot. It is the sort of Mozart passage about which Alfred Einstein might imagine Mozart musing, “How in the world did I do that?”

Our performance should properly shock Mozart scholars who have decided that the text of the last movement as first printed is wrong, that the ubiquitous theme is a write-over in a non-Mozart hand, and should be, instead of the infectious jagged descent, just a chromatic scale. We disagree.

Our performance was a celebration of a friend of our festival, violin-maker-physicist W. F. (“Jack”) Fry of the University of Wisconsin Physics Department: all the instruments except the cello are of his making. A regular part of the Token Creek Festival has been the series of varied forums covering diverse topics such as Text and Music, Modes of Thought: Scientific and Artistic, Shakespeare, ecological restoration. Most central to our purpose were a popular series on the Acoustics of the Violin, led by Jack Fry (who also presented his research, with Rose Mary Harbison, on PBS Nova and at the Smithsonian, Boston Museum of Science, and MIT). It is impossible to summarize briefly Fry’s original and very convincing work as a physicist-violin maker. Roughly put, Fry has shown that varnish, wood, age and mystique are secondary considerations in the continuing hegemony of the great violins made in the early 1700s. Instead, the inner graduations – the thickness of the wood, to the most minute measurement – determines the quality of the sound. The secrets of these controls, long lost because of guild and family rivalries, Fry sought to demonstrate with his own instruments. It was challenging to play this very detailed piece on unfamiliar instruments, but it made the occasion redolent of our ongoing interest in exploring, along with our musical repertoire, related disciplines.

The Piano Concerto in A major, K. 414, is one of those playable either with orchestra of by a reduced ensemble. It is, from start to finish, a music as natural as breathing, a steady flow of oxygen and other sources of nourishment. Its character is always intimate and cordial, its melancholy rare, and its inspiration steady. Not even the last, most mature concertos have a more easy flow, or consistent warmth than this one.

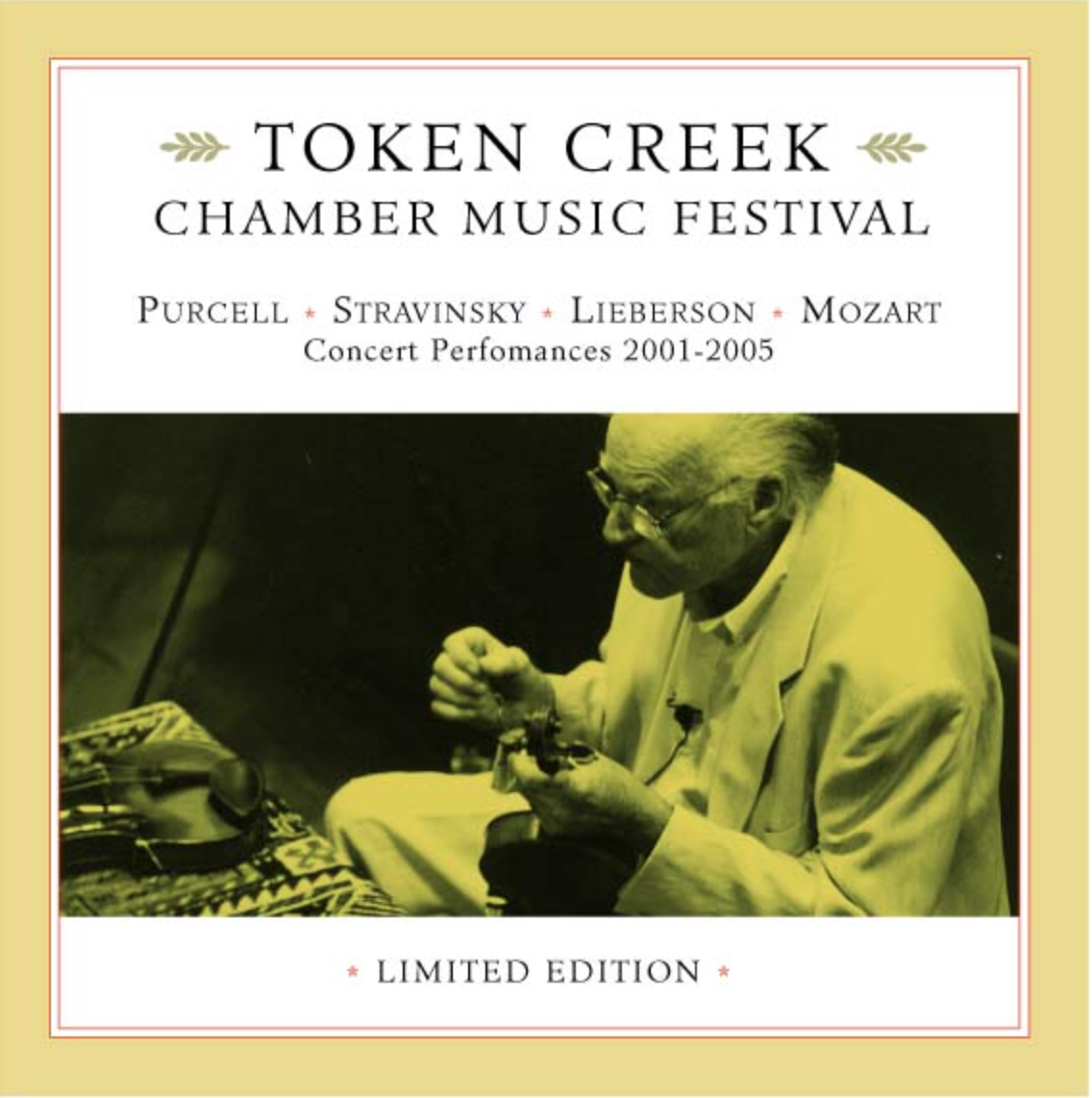

Available on CD

TCR 111: Purcell – Stravinsky – Lieberson – Mozart

features Mozart’s Quintet for Strings in D Major, K. 593 (from today’s program), performed on Jack Fry instruments at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, Madison, Wisconsin.

This unique, limited-edition recording of live performances from our 2001-2005 seasons is available for purchase from our online store while supplies last.

Click here to order.