TCF 2020 Virtual Season · Music from the Barn

Schoenberg & His Circle

Program

Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19 (1911) Arnold Schoenberg (1864-1951) Leicht, zart Langsam Sehr langsam Rasch, aber leicht Etwas rasch Sehr langsam- Leonard Stein, piano

- from the 1997 Token Creek Festival

- Leonard Stein, piano

- from the 2000 Token Creek Festival

- Kendra Colton, soprano

- Judith Gordon, piano

- from the 1996 Token Creek Festival

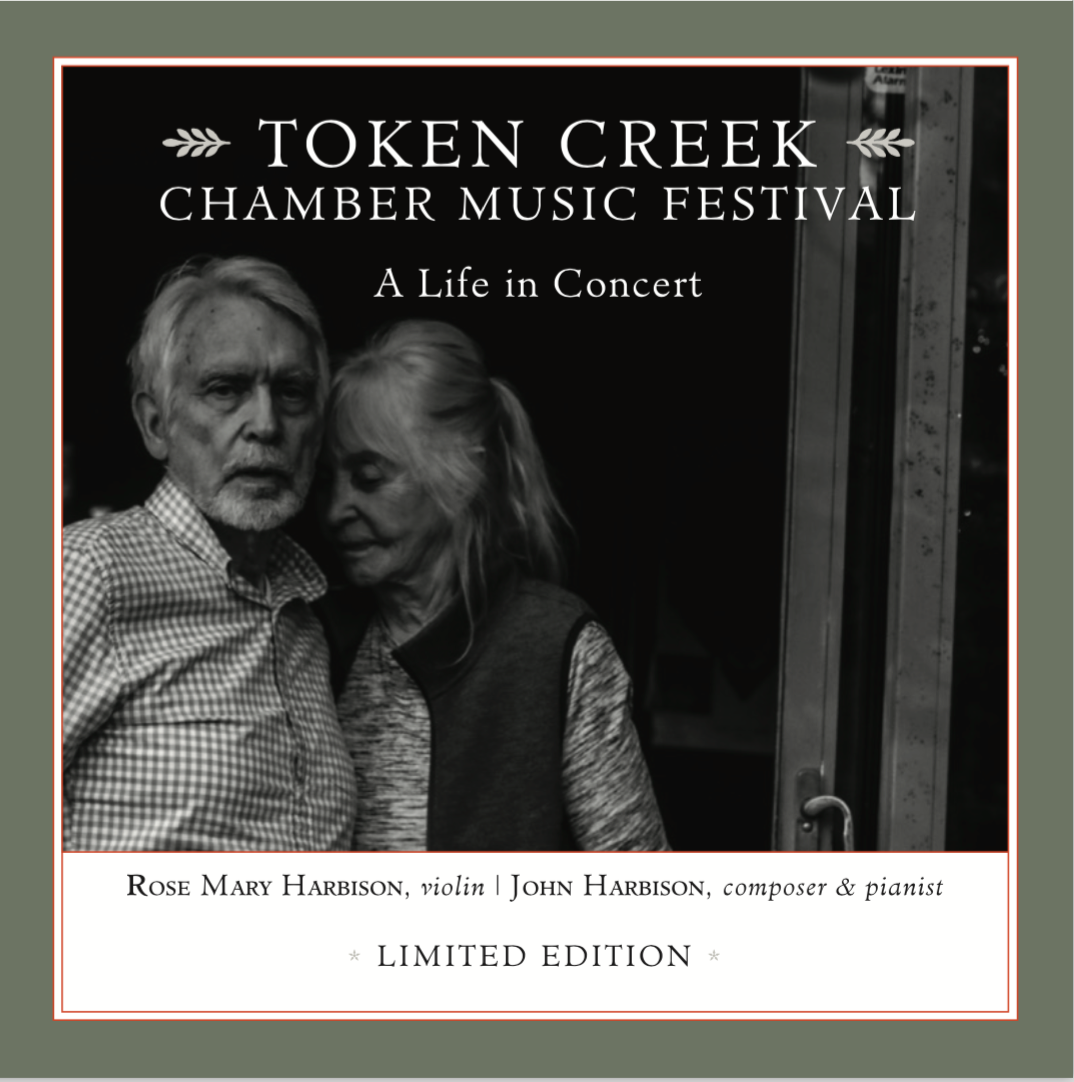

- Rose Mary Harbison, violin

- John Harbison, piano

- from a 2008 Token Creek Festival studio session

- Rose Mary Harbison, violin

- Leonard Stein, piano

- from the 2004 Token Creek Festival CD Leonard Stein in Memoriam

Program Notes

Schoenberg is a name that has the capacity to strike fear into the ears of some listeners, but at the Token Creek Festival we take an unusual interest, satisfaction, and pleasure in his music, which we have been exploring since the performance of his controversial Ode to Napoleon at our inaugural concert in 1989. In particular, Rose Mary Harbison’s close associations with violinist Rudolf Kolisch (an ardent proponent of the Second Viennese School, who had studied composition with Schoenberg and later became his brother-in-law) and with pianist Leonard Stein (Schoenberg’s student, then assistant, then director of the Schoenberg Institute, editor of Schoenberg’s important treatises, and writer about his music) led to memorable concerts in the barn.

Leonard Stein was five times a participant in the Token Creek Festival, 1994-2000. He was a great favorite of our audiences. Each occasion was unique, an encounter with a singular musical spirit, connected to the “great tradition,” endlessly curious about the present. “He was a no-nonsense pianist. . . adamantly not a demonstrative player. He valued clarity above all, and he had the rare ability to make immediate sonic sense of structurally complex music.” (Mark Swed, LA Times). Stein’s formidable performances of all repertoire were revelatory — no one who was there in the barn that night will ever forget his 1997 “Hammerklavier” sonata.

This program is organized around extant recordings of Leonard Stein available in the Token Creek archives: music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Busoni. We hope that your ears will find it as fascinating as we have.

Arnold Schoenberg’s historical significance as the father of serialism often obscures the true variety of his output. It also tends to minimize the purely musical (i.e. non-theoretical) aspects of his compositions, regardless of their style. Schoenberg’s idiosyncratic and original piano writing is evident in these two very different sets of piano pieces, Op. 19 (1911) & Op. 23 (1923).

“Anyone writing for piano should never forget that even the best pianist has only two hands. . . . The only way is to write as thinly as possible: as few notes as possible.” (Arnold Schoenberg: Der moderne Klavierauszug, 1923) This epigraph reveals one of Schoenberg’s central concerns in composing for the piano: he constantly strove for clarity through the most efficient means of expression.

With their miniature format and extreme aphoristic brevity, the six Op. 19 pieces might appear to be a strange and confusing departure from Schoenberg’s normal concise formulation, but they are wholly symptomatic of the free-tonal form of his works. The first piece, just seventeen bars long, consists of melodic nuclei that do not come together into a phrase but are heard one after the other, like disjointed thoughts. In the next piece, the rhythmic ostinato of repeated major thirds assures a far greater degree of stability, as though the composer had now underpinned the piano writing with tonality. In the third piece, the right and left hands develop in independent dynamic frameworks, thus forming a contrast with each other, in a very fragmented way. The next two pieces can be perceived as a combination of recitative and aria.

Although Schoenberg was not a pianist himself, but he had distinct aural expectations of his works for the instrument, and he found the medium conducive to working out and conveying the essence of his musical ideas. His twelve-tone method appeared slowly between 1916 and 1923, and it is the fifth piece of the Op.23 set, the ‘Walzer,’ that constitutes the composer’s first strictly dodecaphonic page.

These pieces are far more expansive than the miniatures of Op. 19, and regardless of the atonality, it is the lyric strand that is paramount here.

(Thanks to the Arnold Schoenberg Center and Gary Higginson, MusicWeb International for notes and thoughts on Op. 19 & Op. 23.)

Berg, considered by many to be the most traditional, perhaps most romantic of the Second Viennese group of composers, wrote the Seven Early Songs between 1905 and 1908, the product of his years of apprenticeship to his mentor Arnold Schoenberg. They do not form an integrated cycle — each sets a poem by a different author. Mark DeVoto points out that the Seven Early Songs have a strong motivic structure; some are built upon a single motivic cell, extensively manipulated and layered. Harmonically, the songs exist in the world of late-Romantic expanded tonality, with a certain ambiguity between major and minor modes, suspension, delayed and sometimes avoided resolutions, and occasionally superfluous key signatures. DeVoto also points out that the Seven Early Songs exemplify a Bergian harmonic tendency, namely “creeping” — that is, harmonic progressions related not by conventional rules but by “stepwise relation and common tones.” This means that, for example, successions of chords may simply be related chromatically, descending or ascending by semitone. The Seven Early Songs also display Berg’s penchant for symmetrical melodic structures, a characteristic evident in the composer’s frequent use of inversion. They possess the sensitivity to text-setting and vocal sonority, the wide-ranging lyricism, the subtle harmonic color and the sincerity of expression that characterize his best music.” (Thanks to Marc DeVoto and Richard Rodda for notes and thoughts on the Seven Early Songs.)

Schoenberg’s Phantasy is a late work and his last instrumental work. It’s very precise original title, “Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment” speaks to the fact that Schoenberg composed the solo violin part first, perhaps intending it initially as a work for unaccompanied violin, and then later wrote a separate piano part to go with it.

The Phantasy, just nine minutes, is an intense, virtuosic rhapsody in a single movement, but containing within it episodes that clearly recall archetypes of other traditional forms, including a complete little Scherzo and Trio crisply bouncing in 6/8 rhythmic games. Schoenberg is meticulous about dynamic and expressive indications, including romantic markings such as passionato, dolce, cantabile, grazioso, and furioso. Variation is a central principle in composing with 12-tone rows, and there is also a very clear sense of theme-and-variations here, including a tight, dramatic recapitulation. (Thanks to John Henken, Los Angeles Philharmonic, for this description.)

Perhaps the one other musician of the era with enough vision and ego to match Schoenberg’s own was Ferruccio Busoni. The “like-minded iconoclasts” had exchanged letters for years: Schoenberg restlessly pursuing the new; Busoni, Italian-born piano-virtuoso and composer settled in Berlin, both seeking the same compositional liberation from tonality. It was in the second violin sonata that Busoni found his mature compositional voice.

Ever combining historicism with a look to the future, Busoni based the second sonata on an earlier work, Beethoven’s piano sonata, Op. 109, adopting its tripartite form: a first movement that starts slowly but eventually introduces faster, contrasting material; a lively second movement in 6/8 time; and a concluding set of variations. The sonata opens with a chordal invocation marked Langsam that is of the type found in many of Busoni’s later works. This leads to a long-breathed, lyrical violin melody set over subtle ebbs and pauses in the piano. The texture eventually changes to one of constant motion propelled by rising and falling arpeggios in the piano. At its height, the movement shifts to B minor and takes on faster, more pointed articulations, but eventually settles into a recollection of the opening motto and other previous motives. Though not labeled by the composer as such, the Presto second movement is generally considered a Tarentella. Taking off on a theme borrowed from the middle of the first movement, the violin assumes a nervous rhythmic energy while the piano busily traverses the keyboard in playful chordal gestures. The opening of the final movement, marked Andante piuttosto grave, provides a sharp contrast to the vitality of the tarantella, even as it revisits its thematic material, as indicated by the composer in the score, “like a memory.” The slow, pensive introduction leads to a statement of a chorale theme, “Wie wohl ist mir,” from the second in the Anna Magdalena Bach Notebook. Busoni’s variations on the chorale theme assume a wide variety of characters, from the nimble to the mysterious, including a variation in minor invoking a bell-like “death motive.”

The work concludes with yet another recollection, first of the opening gestures of the final movement, then with the chordal statement that opened the entire sonata, recast as a benediction. (Thanks to Jeremy Grimshaw for this description.)

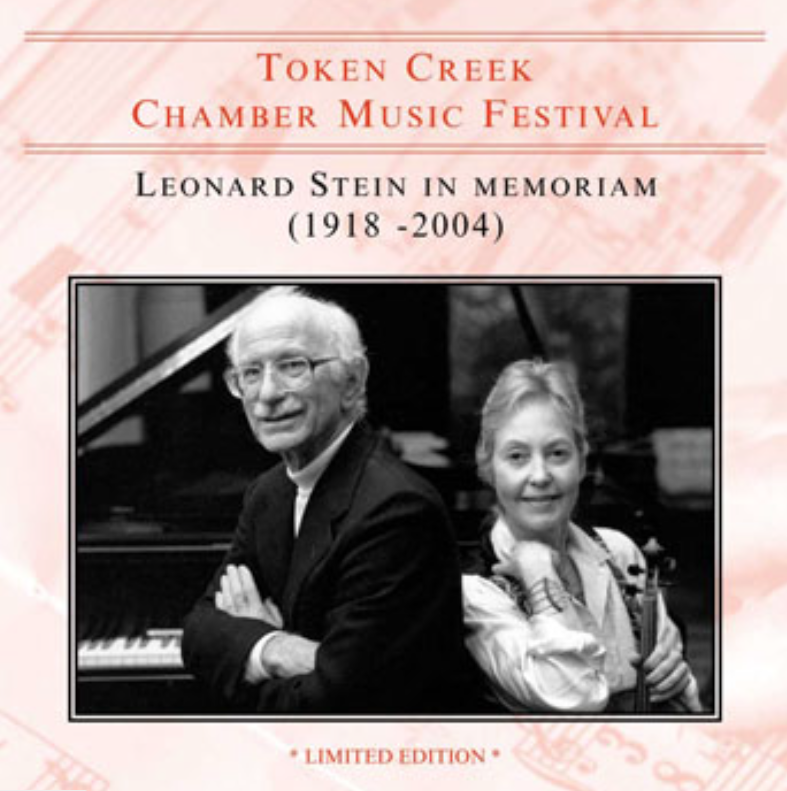

The Leonard Stein in memoriam CD

When Leonard Stein died in 2004, at the age of 87, the Token Creek Festival issued a memorial CD in his honor:

In 1989, at the Schoenberg Institute in Los Angeles, Rose Mary Harbison and Leonard Stein taped a performance of Busoni’s Second Sonata (1898) as a warm-up for a performance and subsequent recording of the piece planned for the following week. A few days later Leonard suffered a heart attack, causing a cancellation of those events. Fortunately, we have the present document: the Busoni was a piece they played often, and their work together here is evidence of a meeting of animated musical minds. From their first meeting at Leonard’s seventieth birthday celebration in 1987 to his death in the summer of 2004, their dialogue produced dynamic performances and vigorous conversations.

Rose Mary Harbison and Leonard Stein met most frequently over common interest in Schoenberg, but Busoni was another shared passion. In the Second Sonata Busoni discovered a lucid, disciplined Romanticism, leavened by his immersion in Bach, untouched by any Mahlerian nostalgia. In certain moments the visionary, futurist Busoni emerges as well, the composer who was one of the first to embrace Schoenberg, even as he wished the music were more immediately apprehendable. (cf. his “pianistic” arrangement of the second of Schoenberg’s Piano Pieces, Op. 11).

Leonard Stein was five times a participant in the Token Creek Festival, 1994-2000. He was a great favorite of our audiences. Each occasion was unique, an encounter with a singular musical spirit, connected to the “great tradition,” endlessly curious about the present. The next thing was always his fondest concern.

The spirit of inquiry has always been a constant element at the Token Creek Festival. In a series of forums on violin acoustics the Festival has been investigating the ground-breaking work of Professor W.F. Fry. Rose Mary Harbison took one of his excellent earlier instruments to Los Angeles in 1989, and it is heard on this recording.

– John Harbison (summer 2004)

This unique, limited-edition recording is available for purchase from our online store while supplies last.

Click here to order.